Todd Erickson in his essay Kill me Again: Movement becomes a Genre (in Silver & Ursini), discusses the emergence of noir motifs in films subsequent to the canonical period and suggests studying them as a new genre. “Contemporary film noir is a new genre of film. As such, it must carry the distinction of another name; a name that is cognizant of its rich noir heritage, yet one that distinguishes its influences and motivations from those of the bygone era” (pg. 321). Erickson proposes the term neo-noir because he identifies the films as new forms of noir. Thus neo-noir is “quite simply, a contemporary rendering of the film noir sensibility” (pg. 321). The neo-noir films, according to Richard Martin in his book Mean Streets and Raging Bulls, “not only [..] suggest noir’s continuing exploration of the collective anxieties of American society, but [..] also reflect a sustained tradition of artistic creativity and technical virtuosity nurtured within the confines of American genre cinema” (pg. 6) However, all attempts to validate the term neo-noir and its relation to film noir, deal with, what are by necessity, delicate boundaries considering that the subject of analysis is one of Hollywood’s most unstable genres.

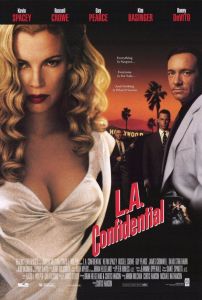

Based on research into neo-noir, I would suggest that there are four basic types (if not more) of production. The first, perhaps the easiest to identify, are those films that constitute a remake of canonical films such as D.O.A, Farewell My Lovely and The Postman Always Rings Twice. The second is that which carries an inflection of nostalgia and make explicit reference to the style and the mood of noir, amongst which are titles such as, Chinatown and L.A. Confidential. The third kind could be identified as those films that pay homage to noir by making references to motifs, dialogue and scenes, such is the case of Pulp Fiction and generally of the work of Quentin Tarantino. The fourth category of neo-noir is perhaps the most difficult to define as all the films I have previously mentioned are examples in which film noir is deliberately referenced. This ‘group’ holds films that do not fit in to any of the aforementioned ‘categories’ and yet audiences can easily perceive certain tropes of noir within these films. Among these we find examples of films as diverse as Matrix, Blade Runner, Lost Highway, Basic Instinct and Black Rain.

Erickson, in his essay accuses two films: The Two Jokes (1990) and The Public Eye (1992) of failing “to maintain the slightest notion of the true noir spirit” (pg. 312). Although the question of truth is problematic Erickson succeeds in adding to the lists of noir definitions the word “spirit”. What defines then the noir spirit? Could it be the “cynical and the pessimistic tone […] the darker side of human condition, modern fables that highlight the dangers of alienation, the fragmentation of society, the breakdown of human interaction, the debasement of love, the beguiling power of wealth, the corruption of government, and mankind’s inherent propensity for inertia and impotence” (Martin, pg. 6)? Is noir “spirit” allowed to evolve, mutate as the environment in which it exists changes? It is also entitled to refer and quote to the noir canon since contemporary audiences are not only conscious of the legacy of noir but also amenable to noir references in modern perspectives and environments?

When discussing authenticity the Argentinean poet Jorge Luis Borges once stated that being original was a matter of having a good memory. Implying that, in art at least, we are the sons of history and beholden to an artistic past. Any attempt to deny the influence of, and our indebtedness to, past artists and art is to forfeit a valuable resource.