Mise-en-scene is a French term used in film and theatre that literally means, “putting into the scene”. Since it is usually the director (metteur en scene) who has the power over what happens in the movie, one could say that the mise-en-scene is one of the ways in which the director exercises his “control over what appears in the film frame” (156). Some of the aspects of the mise-en-scene include: setting, lighting, costume, and generally all of the actions involved in the take. Some directors may allow their actors to improvise their performances (Altman, Sayles, Renoir) in order to allow more spontaneity. However, this spontaneity is also part of the director’s view of how the scene should go, and allowing improvisation does not lessen his/her control over the scene.

French entrepreneur George Méliés built the first film studios, in order to create atmospheres and settings for his films. Shooting in a studio gave him more (if not complete) control over every element of the frame. Among the first person narrative films ever made are science fiction and fantasy short films.

In order to analyze what takes place in the mise en scene BT (Bordwell & Thompson), propose analyzing the elements that compose it.

Setting:

The filmmaker can choose to create a setting (like Meliés did or the way films were made back in Hollywood’s golden era) or to use an already existing location. Using a studio may give more control over the shooting and it certainly allows filmmakers to create environments for their films, especially when the story takes place in another era or if it takes place mostly indoors.

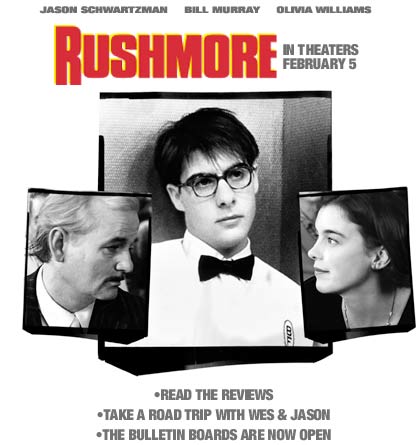

Although “realism” is something that audiences and critics may be concerned about, some film directors can choose to work on un-realistic settings such as Tim Burton’s Batman, or Wes Anderson’s Rushmore. The latter to a lesser degree than the first, but to a certain extent, his exaggerated settings seem adequate for the movie, and for Max, for it certainly adds and “larger-than-life” feel to it.

Choosing to shoot in black and white or in color is also an important decision that can be considered as part of the setting. As we will see later on, filmmakers chose to work with certain color palettes.

Costume and Make-Up:

Like the “setting, costume [and make-up] can [also] have specific functions in the” film. Costumes can play a very important role in the narrative as they can also reveal a great deal of information about the characters. Filmmakers may also choose to dress their characters according to the settings and vice versa. As BT explain, make-up was “originally a necessity because actors’ faces would not register well on early film stocks” (163). However, avoidance of make-up is a choice that directors can take nowadays, like Peter Sollett does in his film Raising Victor Vargas. His avoidance of make-up as well as the close ups he does on his teenager actors, helps audiences come closer to his characters as we are all able to relate to the puberty revealed in their faces.

Contemporary audiences tend to associate make-up with extravagant make-up sessions and costumes such as the ones used in horror and science fiction films. However, most actors use make-up, this is the reason why when a director chooses not to use it on his actors we are able to notice the difference, even though we might not be aware of it.

Lighting:

One could argue that lighting is among the most important aspects of filmmaking, since “much of the impact of the image comes from its manipulation of lighting”. Filmmakers compose the image around light, darkness and shadows in order to draw our attention to certain objects or actions. “Lighting can also articulate textures: the soft curve of a face, the rough grain of a piece of wood”, (164) etc.

BT isolate “four major features of film lighting: its quality, direction, source, and color”. The quality refers to the intensity of the illumination. “Hard” light casts strong shadows enhancing that which is illuminated, while “soft” lighting creates a subtle and more benign illumination. The direction refers to the place from where the object is being illuminated. Among such lighting techniques are: frontal lighting, giving little shadows and as a result the image can be very flat; sidelight or cross-light, used to sculpt objects or faces; backlighting, coming from behind the image (which can also be positioned at many different angles); under lighting, when the light comes from below the object; top lighting, where the spotlight is placed almost directly above the object; and source lighting, where the light comes from a prop (lamp, etc) or when the light that is used comes from the light available in the surroundings. However, in most cases filmmakers choose to use different sources of lighting that can come from different directions.

Like in Film Noir, lighting can be used as a motif in the course of a film. It can also be used with colored filters to increase dramatic effect.

Staging: Movement and Acting:

As stated earlier some directors allow their actors to improvise while others inform them exactly what they want out of a scene. Facial expressions, appearance, gestures and body language also play a huge role in the mise en scene. Again, the question of realism comes to play here but as audiences we should ask ourselves not how real the acting is, but rather how well does it suit the narrative. This responds to the fact that audiences perceptions change over time, and that in some cases, histrionic and “un-realistic” acting could well be the “acting style that the film is aiming at” (171). (Think of Jim Carey’s persona in most of his leading roles, for example). At the end of this section BT reminds us that: “as with every element of film, acting offers unlimited range of quite distinct possibilities. It cannot be judged on a universal scale that is separate from the concrete context of the entire film’s form.” (174)

All the components above mentioned are part of what we understand as the mise en scene. These elements will go under changes and transformation that occur in both time and space.

Space:

Film directors are aware of the fact that our vision reacts to changes in “movement, color, differences, balance of distinct components, variations in size”(176), color contrast and our sense of screen space. The mise-en-scene is therefore arranged taking all these visual components into account creating a particular screen space. In most cases the screen space represents the three-dimensional space in which the action occurs, and it is sued to add dramatic effect but also as a tool to direct our attention towards what the film director considers important.

Another resource that filmmakers use in order to add dramatic effect is the use of color. Earlier on BT mentioned the use of color filters when discussing lighting, however, sometimes a director may choose to work on a limited “color palette”, in order to enhance our ability to perceive changes in screen space, or simply to add dramatic effect. Take Rushmore, for example. Anderson chooses to dress Max in tones that stand out agains the plain clothes that others chose to wear (his Rushmore jacket, or the green velvet outfit he wears after he is expelled from school). (We should also be aware of the fact that black and white movies can also exploit their shades of grey, and that color can also play a big role in such films).

Another crucial element here is the way the director chooses to capture the screen space, the angle at which he/she places the camera, as well as how the elements in the shot are arranged, play a huge role in how we relate to the scene. This will also affect the spatiality of the shot since it can reveal shallowness in space or a depth.

Time:

Apart from visual components, the shot also has a duration that corresponds to the director’s sense of rhythm. Many directors, like Jacques Tati for example, choose to accentuate the scenes by giving different speeds to different simultaneous actions. Another example could be the use of slow and fast motion, for example, when Max leaves the hotel after he has infested Herman´s room with bees. The slow motion accentuates the bold move from Max´s part.

The notion of depth of space is also relevant to the “time” since the same depth of space can reveal different actions that involve time. In BT’s words: “Our time-bound process of scanning involves not only looking to and fro across the screen but also, in a sense, looking “into” its depths. A deep-space composition will often use background events to create expectations about what is to happen in the foreground”. (182)

Be First to Comment